A very Brief History of Bread

Sourdough simply refers to any bread made using a natural culture of wild yeasts and lactic acid bacteria (known as a sourdough starter) to slowly ferment the dough.

Our sourdough starter at La Cuisine Des Hayeks is only made of two ingredients organic freshly milled whole wheat flour and water.

Sourdough can come in many forms—not just tangy, crusty loaves. It can also include fluffy brioche or even laminated pastries like croissants, which aren’t typically thought of as "sour." Because of this, some people feel that the term "sourdough" is misleading and might be better named "naturally fermented bread" to distinguish it from bread made with baker’s yeast (commercial yeast or fast-acting yeast).

In its purest form, sourdough contains just three simple ingredients: flour, water, and salt.

The sourdough starter, which is used to leaven the bread, is made by mixing flour and water and capturing wild yeast and bacteria from the environment—like the air and the surface of grains. This means the yeast and bacteria strains in sourdough starters can vary significantly from region to region and baker to baker, giving each one its unique characteristics. In fact, a sourdough library in Belgium has been preserving and studying sourdough cultures from around the world since 2013. So far, over 700 strains of wild yeast and 1,500 species of lactic acid bacteria have been cataloged.

Some of the yeast and bacteria in sourdough cultures are found nowhere else.

Sourdough bread is sometimes called "slow bread" because the fermentation process is much longer than bread made with commercial yeast. While bread made with commercial yeast can be ready in just a couple of hours, sourdough bread requires many more hours to ferment and rise no less than 12-14 hours.

This slow fermentation process is what gives sourdough its unique flavor and texture, making it different from faster-made breads.

In the next section, we will briefly discuss the benefits of sourdough and why it’s important to let the bread ferment naturally for a longer period.

What is Sourdough bread?

Sourdough simply refers to any bread made using a natural culture of wild yeasts and lactic acid bacteria (known as a sourdough starter) to slowly ferment the dough.

Our sourdough starter at La Cuisine Des hayeks is only made of two ingredients organic freshly milled whole wheat flour and water.

Sourdough can come in many forms—not just tangy, crusty loaves. It can also include fluffy brioche or even laminated pastries like croissants, which aren’t typically thought of as "sour." Because of this, some people feel that the term "sourdough" is misleading and might be better named "naturally fermented bread" to distinguish it from bread made with baker’s yeast (commercial yeast or fast-acting yeast).

In its purest form, sourdough contains just three simple ingredients: flour, water, and salt.

The sourdough starter, which is used to leaven the bread, is made by mixing flour and water and capturing wild yeast and bacteria from the environment—like the air and the surface of grains. This means the yeast and bacteria strains in sourdough starters can vary significantly from region to region and baker to baker, giving each one its unique characteristics. In fact, a sourdough library in Belgium has been preserving and studying sourdough cultures from around the world since 2013. So far, over 700 strains of wild yeast and 1,500 species of lactic acid bacteria have been cataloged.

Some of the yeast and bacteria in sourdough cultures are found nowhere else.

Sourdough bread is sometimes called "slow bread" because the fermentation process is much longer than bread made with commercial yeast. While bread made with commercial yeast can be ready in just a couple of hours, sourdough bread requires many more hours to ferment and rise no less than 12-14 hours.

This slow fermentation process is what gives sourdough its unique flavor and texture, making it different from faster-made breads.

In the next section, we will briefly discuss the benefits of sourdough and why it’s important to let the bread ferment naturally for a longer period.

Benefits Of Sourdough Fermentation

Here are the main benefits of bread made using sourdough fermentation. If you would like to learn more, each of these benefits will be explained in detail below.

1. Improved Digestibility and Access to Nutrition

Grains, as seeds, evolved to protect their nutrients, which are only released when the seed begins to germinate. This protection comes from a substance called phytic acid, which binds essential minerals like zinc, magnesium, calcium, and iron. When we consume grains, phytic acid can hinder our ability to absorb these nutrients, making grains harder to digest.

Phytic acid is the primary way plants store phosphorus, and it also binds to several minerals, including zinc, magnesium, calcium, and iron. When phytic acid binds with a mineral in the seed, it becomes what’s known as a ‘phytate.’ As the seed starts to prepare for germination, an enzyme called ‘phytase’ is activated, which breaks down the phytates and releases their bound nutrients.

Some animals, particularly ruminants like cows, sheep, and goats, have evolved to digest grains and extract nutrients from them by fermenting the grains in a specialized stomach. This fermentation, mainly driven by microbial action, produces phytase, which breaks down the phytates.

Humans, however, lack this ability. As a result, eating grains can lead to issues with nutrient absorption and even intolerances.

Phytic acid doesn't just limit nutrient availability by holding onto them—it can also bind to other nutrients it encounters. This makes it an ‘anti-nutrient,’ as it not only hinders the absorption of nutrients found in grains but can also inhibit the absorption of other minerals from different food sources within the digestive system.

So, if humans can’t simply eliminate phytates, how can we overcome the digestive challenges they cause? The trick is to simulate the conditions that would prompt the seed to germinate, which can be achieved through fermentation, specifically using a sourdough culture.

The lactic acid fermentation that occurs during sourdough preparation activates phytase, which breaks down the phytates and releases the bound nutrients. This makes the grains much easier to digest and far more nutritious.

Beyond neutralizing phytates, the acids produced by sourdough bacteria trigger the activation of a variety of enzymes. Complex carbohydrates are broken down from starches into simpler sugars, and long protein chains are broken down into their constituent amino acids. One of these proteins is gluten. Gluten, found in several grains, is the protein that gives dough structure and allows gases to be trapped, causing the dough to rise. Recently, gluten and bread have received negative attention, with some claiming that they have harmful effects on health.

However, recent studies suggest that the rise in gluten intolerance may be linked to the fact that modern breads often don’t undergo extended fermentation. Without this process, grain proteins, like gluten, remain intact and can be harder to digest.

Additionally, modern breads often contain extra gluten, added to enhance the dough’s elasticity and improve its ability to capture gas. Since sourdough fermentation partially breaks down gluten, it reduces some of the peptides believed to trigger gluten intolerances. This is why some individuals with gluten sensitivity have been able to tolerate sourdough bread without problems (note that gluten intolerance is different from celiac disease, which is a severe allergic reaction to gluten).

Sourdough fermentation also helps neutralize another substance known as lectins.

Lectins are proteins found in many foods, including grains. While some lectins can be beneficial, others act as anti-nutrients, interfering with nutrient absorption and irritating the intestines.

The acids produced by the lactic acid bacteria during fermentation play another vital role. They initiate digestion even before the bread reaches your stomach by triggering your mouth to produce saliva, which contains enzymes that begin breaking down starches. Unlike the dry sensation often experienced with commercially produced bread—where you find yourself reaching for a glass of water—sourdough helps prevent this by starting the digestive process right from the first bite.

2.Lower Glycemic Index

The glycemic index (GI) is a measure that ranks foods on a scale of 1 to 100 based on how quickly they raise blood glucose levels.

Many modern breads, particularly white and highly processed varieties, have a high glycemic index, meaning they cause a rapid spike in blood sugar due to the quick digestion of starches.

In contrast, the fermentation process in sourdough appears to lower its GI. During fermentation, the yeast and bacteria in the culture consume some of the starches and sugars in the flour, and the acids produced during this process seem to slow the rate at which glucose is absorbed into the bloodstream.

3.Complex flavor development and robust texture

The transformation of flour into bread is driven by the metabolic by-products of various microbes.

Yeast and bacteria produce carbon dioxide, which causes the bread to rise, while ethanol released by the yeast contributes to the bread’s aroma. The acids produced by the bacteria play several vital roles: they enhance flavor, strengthen the dough, and, as mentioned earlier, improve the digestibility of grains. Additionally, these acids help bring out a fifth flavor category called umami, which the Japanese recognize alongside sweet, sour, salty, and bitter. Natural fermentation is one way to unlock a wide range of umami flavors.

In sourdough, lactobacilli bacteria outnumber yeast by a factor of 100 to 1, and it’s the acids from these bacteria that generate aromatic compounds, infusing the bread with flavor. The flavors in sourdough come from the microorganisms fermenting the flour, not from the flour itself.

On the other hand, bread made with commercial yeast contains just one type of yeast, resulting in a less complex flavor. To compensate, industrial bread often includes additional ingredients, like sugar, to enhance flavor.

Highly processed bread also differs in texture compared to traditionally fermented bread. When you roll up a piece of processed bread, it sticks together into a tight ball and almost returns to its dough form. In contrast, sourdough has a much more resilient structure. For example, if you flatten a sourdough loaf, it will bounce back and retain its shape. Do the same with a loaf of commercial bread, and it won’t maintain its structure. This robust texture gives sourdough its satisfying, chewy bite.

4.Production of natural preservatives

The lactobacilli bacteria in sourdough produce organic acids and antibiotic compounds that help prevent the growth of competing microbes, effectively protecting the culture.

This natural biochemical defense also acts as a preservative, extending the shelf life of the bread.

There’s a direct link between a bread's acidity and its ability to last longer. As acidity rises, so does the bread’s shelf life. In the past, rural Europeans would bake bread only once every two to four weeks, and the only bread that could naturally last that long was sourdough, due to its high acidity.

The Art of Milling: Why Fresh, Whole-Grain Flour Makes the Best Bread

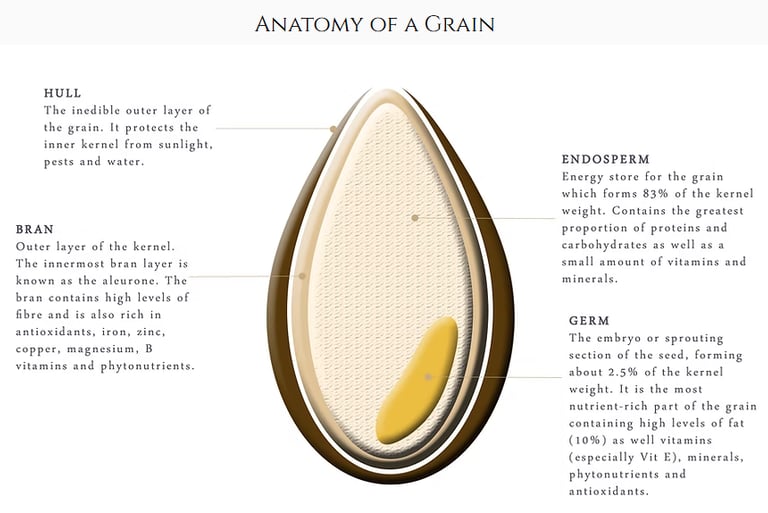

As shown in the diagram above, although the germ makes up only about 2.5% of the kernel's weight, it is the most nutrient-dense part of the grain, containing high levels of vitamins, minerals, and healthy fats. The germ is the embryo of the grain, from which the roots and shoots of a new plant will emerge when the grain germinates.

The germ’s richness in unsaturated omega-3 fats contributes to its nutritional value, but it also makes it unstable. Once the grain is milled into flour, the fats can turn rancid, shortening the shelf life of the flour. While stone-ground flour retains the germ, it removes the bran (the outer layer), so fresh milling is essential. Historically, every town had its own mill to ensure a steady supply of freshly milled flour.

The development of roller-milling in the mid-19th century revolutionized flour production, making white flour cheaper, whiter, and more stable. This process removes both the germ and the bran, leaving only the endosperm to be ground into flour. By removing the germ, the flour’s shelf life can be extended indefinitely.

Even when making whole-wheat flour, roller-milling still removes the germ and bran at the start of the process because the oils in the germ can clog milling machinery. Most commercial whole-wheat flour is actually white flour with the bran and germ added back, but some mills may only include part of the bran, leaving out the germ. If this is the case, the flour isn’t truly "whole" and its nutritional value is compromised.

Roller-milling also strips away the aleurone layer, the innermost part of the bran, which is rich in nutrients and antioxidants. In stone-ground flour, the aleurone layer is preserved and remains integrated with the endosperm.

Once a seed is milled or opened in any way, it enters a phase of rapid oxidation, losing the energy and nourishment it could have provided. This is also when the flavor is at its peak before it begins to fade. Freshly milled whole-grain flour has a sweet, fragrant aroma, and the word "flour" itself comes from the term "flower," referring to the finest portion of ground grain. This spelling was used until the 1930s when "flour" became the standard to avoid confusion.

Whole-grain breads, while packed with nutrition, tend to be denser because of the coarse fiber in the bran. The bran pieces act like tiny shards that cut through the gluten network, making it harder for the dough to trap air, resulting in a heavier loaf compared to those made with refined flour.

Enzymes – Wheat berries contain natural enzymes that aid processes like starch conversion and yeast fermentation. These enzymes are mostly lost in processing. Fresh-milled retains all the active enzymes.

At La Cuisine Des Hayeks, we never use refined white flour in our bread. Instead, we mill our own fresh flour on the same day we bake. Our bread is rich in fiber, thanks to the bran, and contains the full germ of the grain, which is packed with natural vitamins and minerals—there’s no need to artificially enrich our flour. To help explain why this is important, I’ve included a brief explanation of the anatomy of a wheat grain.